Warts in Primary Schoolchildren: Prevalence and Relation With Environmental Factors

F.M. van Haalen; S.C. Bruggink; J. Gussekloo; W.J.J. Assendelft; J.A.H. Eekhof Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Background: Warts are very common in primary schoolchildren. However, knowledge on wart epidemiology and causes of wart transmission is scarce.

Objectives: To determine the prevalence of warts in primary schoolchildren and to examine the relation with environmental factors in order to provide direction for well-founded recommendations on wart prevention.

Methods: In this cross-sectional study, the hands and feet of 1465 children aged 4-12 years from four Dutch primary schools were examined for the presence of warts. In addition, the children's parents completed a questionnaire about possible environmental risk factors for warts.

Results: Thirty-three per cent of primary schoolchildren had warts (participation rate 96%). Nine per cent had hand warts, 20% had plantar warts and 4% had both hand and plantar warts. Parental questionnaires (response rate 76%) showed that environmental factors connected to barefoot activities, public showers or swimming pool visits were not related to the presence of warts. An increased risk of the presence of warts was found in children with a family member with warts [odds ratio (OR) 1.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3-2.6] and in children where there was a high prevalence of warts in the school class (OR per 10% increase in wart prevalence in school class 1.6, 95% CI 1.5-1.8).

Conclusions: One-third of primary schoolchildren have warts. This study does not find support for generally accepted wart prevention recommendations, such as wearing protective footwear in communal showers and swimming pool changing areas. Rather, recommendations should focus on ways to limit the transmission of wart viruses within families and school classes.

Introduction

Warts are very common in primary schoolchildren and frequently result in discomfort. However, knowledge on wart epidemiology is scarce. Available studies on wart prevalence in schoolchildren are outdated, poorly designed, or restricted to investigations of dermatology outpatients or specific ethnic groups.[1-8] With these shortcomings, the reported overall prevalence of warts ranges from 3% to 20%. One recent, high-quality study carried out in Australia reported a prevalence of 22%.[9] However, based on entries in general practice registers in the Netherlands, the prevalence of warts presented to general practitioners (GPs) over a year is approximately 6% in schoolchildren.[10]

To prevent warts, official authorities such as national and municipal health services as well as GPs provide recommendations, e.g. to wear 'flip-flops' in public showers and in swimming pool changing areas.[11,12] These recommendations are based on the assumption that wart viruses are spread by contact with the floors of public showers, gyms and swimming pools. However, evidence supporting such assumptions is limited and contradictory.[7,13-18]

The aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine the prevalence of warts in primary schoolchildren and to explore whether contact with an infected environment promotes the presence of warts, thereby providing direction for evidence to base recommendations on wart prevention.

Materials and Methods

In the summer and autumn of 2007, an extensively trained medical student (F.M.v.H.) inspected the hands and feet of all children in grades 1-8 (4-12 years of age) from four primary schools around Leiden, the Netherlands. All children were eligible, and no exclusion criteria were used. Parents were asked to give informed consent for their children and children were free to refuse during examination regardless of parental consent. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Leiden University Medical Centre.

Location, size and number of warts were recorded on standard forms with schematic representation of hands and feet. In addition, the skin type was coded to stratify into Caucasian and non-Caucasian subgroups according to Fitzpatrick skin type.[19] Over 5% of examinations were directly supervised by experienced GPs, with no discordance in wart diagnosis.

Before examination, parents were asked to complete a questionnaire about the presence of possible environmental risk factors for warts, including a family member with wart(s),[1,3,5,15,16] number of children in the family (one vs. more),[3] walking barefoot at home, (barefoot) use of public showers,[7,17] practising gymnastics and sports barefoot,[5,15,16,18] and use of public swimming pools.[5,7,14-16,18] The examiner was unaware of the answers in the questionnaires.

Prevalences were compared with X 2 tests. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of all included risk factors. In subgroup analysis, ORs were calculated for children with hand warts and children with plantar warts separately.

Results

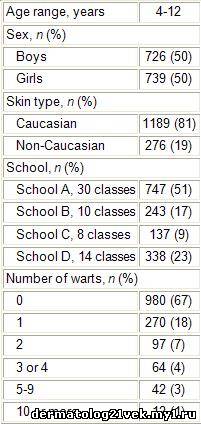

The participation rate for 1526 eligible primary schoolchildren was 96%. Reasons for nonparticipation were lack of child or parental consent (1%) and absence of the child during the examination period (3%). Table 1 shows the sociodemographics of the participants. The overall prevalence of warts was 33% (485 of 1465, 95% CI 31-35%). Most of these children had only one or two warts (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Primary Schoolchildren (n = 1465)

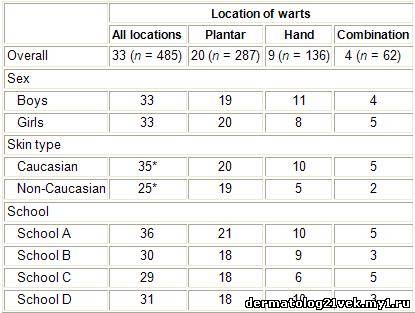

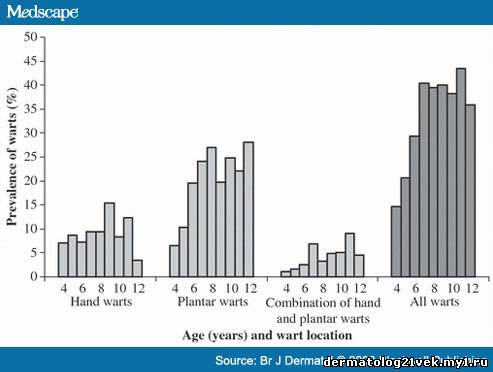

The prevalence did not differ between sexes (P = 0.88) or between schools (P =0.11), but did differ between Caucasian and non-Caucasian skin types (P = 0.002, Table 2). The prevalence of warts increased with age, from 15% in 4-year-old schoolchildren to 44% in 11-year-olds (P < 0.001, Figure 1).

Table 2. Prevalence of Plantar Warts and Hand Warts in Primary Schoolchildren According to Sex, Skin Type and School (n = 1465)a

aValues are percentages. Sum of location prevalences may differ from all locations prevalence, due to rounding off.

*Significant difference (P = 0.002).

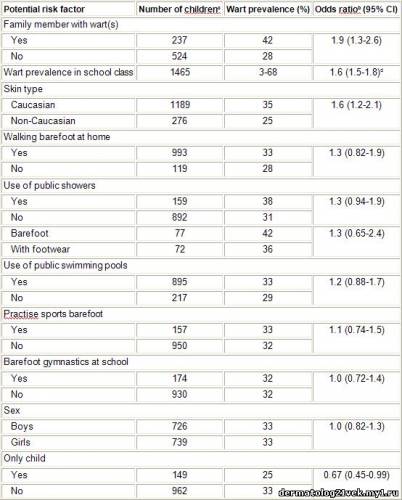

Parents' response rate to questionnaires was 76%. Children with a close family member with warts had an increased risk of having warts (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3-2.6) and children of families with only one child had a decreased risk of having warts (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45-0.99, Table 3). Children with a Caucasian skin type more often had warts than children with a non-Caucasian skin type (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2-2.1). None of the environmental factors related to barefoot activities, use of public showers or swimming pool visits showed a significantly increased risk for having warts. Wart prevalence in different school classes ranged from 3% to 68%; increasing prevalence was correlated with an increased risk of having warts (OR per 10% increase in wart prevalence in school class 1.6, 95% CI 1.5-1.8). Children with hand warts and children with plantar warts separately showed similar ORs for all potential risk factors. In particular, ORs for environmental factors related to barefoot activities did not differ between children with plantar warts and children with any warts.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of warts in primary schoolchildren (n = 1465) according to wart location and age.

Table 3. Personal and Environmental Risk Factors and Their Relation with the Presence of Wartsa in Primary Schoolchildren, Ordered by Odds Ratiob (n = 1465)

aSimilar outcomes were found in subgroup analysis for children with plantar warts.

bUnadjusted odds ratios are reported; adjustment for age did not change any findings.

cSum of numbers per potential risk factor is ≤ 1465, due to differences in response rates (68-100%) to specific questions on parental questionnaire.

dOdds ratio per 10% increase in school class wart prevalence according to logistic regression analysis. CI, confidence interval.

According to parents' responses to the questionnaire, only 17% of children had hand or plantar warts and 4% reported warts in other locations. Parents did not report the presence of warts in 49% of children found with hand warts on physical examination and in 62% of children found with plantar warts.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study on wart epidemiology reveals that one-third of primary schoolchildren have warts on their hands or feet. We did not find support for generally accepted preventive recommendations such as wearing protective footwear in public showers and in swimming pool changing areas. However, primary schoolchildren with a family member with warts or many classmates with warts have a higher risk of having warts themselves. Transmission within families and school classes probably plays an important role.

Our prevalence figures are substantially higher than in previous studies (33% vs. 3-22%), in particular due to substantially higher plantar wart prevalence.[1-9] These conflicting findings may reflect regional differences, may indicate a trend in time or may be due to variations in study design. As we presented, different observation methods will lead to different prevalences; in our study the overall prevalence was 17% by parental report and 33% by examination by experts. These unnoticed warts also explain part of the discrepancy between the prevalence of warts on examination and the proportion of schoolchildren consulting a GP for advice on treating warts (approximately 6% per year[10]).

We found an increase in the prevalence of warts with age in which the prevalence seems to level off at age 9-12 years. In accordance with others,[1,17] we found a lower prevalence in children with a non-Caucasian skin type (mostly originating from Morocco, Turkey, China, the Netherlands Antilles and Surinam).

Human papillomavirus colonization is universal and occurs very early in life. Subsequent exposure of the immune system to different, distinct wart virus subtypes during life may promote warts to develop.[20] This multiple subtype exposure may be facilitated by barefoot activities such as swimming, using public showers and practising sports barefoot. Previous studies have indicated that these barefoot activities may relate to the transmission of wart viruses among individuals.[7,14,17,18] Based on these assumed associations, recommendations such as wearing 'flip-flops' in communal showers and covering warts when swimming were issued.[11,12] However, we could not find support for such recommendations. Our results suggest that wart viruses among children mainly transmit within families and school classes. Conceivably, besides exposure to multiple wart virus subtypes, a critical amount of localized infection load is needed to develop warts. This may be present in families and (to a lesser extent) in school classes but may not be sufficiently present in public showers, swimming pools or gyms. A genetic explanation for the higher presence of warts in some families is not likely, as the risk of warts was also higher with increasing prevalence of warts within classes. However, the cross-sectional design of our study allows us only to examine correlations between risk factors and the presence of warts. Prospective studies are needed to confirm possible causal associations.

Our study population is representative of present-day primary schoolchildren in Western Europe. It was sufficiently large and population based, with similar prevalence rates of warts across different schools and with a participation rate of 96%. We restricted examinations to hands and feet only, potentially missing warts on other parts of the body. However, a previous study showed that only 4% of all warts are located in places other than the hands or feet,[6] suggesting that we missed very few warts. Parental assessment of environmental risk factors for warts may have influenced the outcomes of our study.[7,9] However, more than half of all parents of children with warts were not aware of their children's warts.

In conclusion, warts are highly prevalent in primary schoolchildren. Preventive recommendations should focus on ways to limit the transmission of wart viruses within families or school classes. Furthermore, prospective or intervention studies are needed to demonstrate whether other preventive measures, such as covering warts within families and classes, are effective in interrupting transmission, thereby facilitating a decrease in the present-day high wart prevalence and subsequent discomfort among children.

Главная

Главная  Бородавки у школьников начальных классов: - Форум

Бородавки у школьников начальных классов: - Форум Регистрация

Регистрация Вход

Вход